It was time for some on-the-ground research. Of course, official files from that chaotic time in Germany rarely exist. Eyewitness accounts, if they exist at all, are hard to find. Some soldiers later wrote down their memories from that time, but they were seldom published, and if they were, it is difficult to know which of the authors was in the right place at the right time. Civilian eyewitnesses had little interaction with individual soldiers passing through. Steiner might have left an impression; two Finns in Wehrmacht uniforms not so much. But there was always a chance. And so I wrote to museums, archives and historians in Pritzwalk and Hagenow to ask if they had ever come across stories about Steiner and/or some Finns in their area. The chances were extremely slim from the beginning. And yet, from Hagenow came – not a definitive confirmation, but something that actually fits Törni’s story.

Unfortunately, I don’t know anything about Finnish soldiers who were taken prisoner here. But the town of Hagenow may well be a possibility. On 2 May 1945, US forces occupied this area – including Hagenow. (for example liberation of the concentration camp Wöbbelin near Ludwigslust). A prisoner-of-war camp (more like a mass camp) was set up on the Hagenow airfield. Liberated concentration camp prisoners and liberated prisoners of war and forced labourers were also housed there. The American occupation lasted until 2 June, when the area was occupied by the British. Soviet occupation followed on 2 July. So the „Finnish“ episode must have taken place here between 3 May (captivity of the Finns) and 2 June (handover to the British) or 2 July (withdrawal of the British).

Which is spot-on. The legends surrounding Törni actually mention the Hagenow airfield! I had ignored it until now as it was part of increasingly fanciful stories about Törni’s last days in the war, but apparently they contained a kernel of truth.

In Tyrkkö’s description, Törni fights his way with the remnants of an unnamed „artillery regiment“ through multiple Soviet blockade rings „to an airfield near where they finally met the British troops“. […] According to Kairinen, Törni and his troops excelled in the fighting east of Berlin „but where eventually forced to surrender to an English unit that was about to arrive at an airfield near Berlin.“ The source of Tyrkkö and Kairinen seems to be the same, perhaps Kairinen’s own account, and the unnamed airfield appears in both as a common detail. […] There is no consensus either on who Törni and Korpela surrendered to, or on what happened to them immediately after their surrender. In Kallonen and Sarjanen’s description, Törni and Korpela end up in captivity at the hands of US troops. In both Tyrkkö’s and Kallonen and Sarjanen’s accounts, the Western Allied forces, the British in Tyrkkö’s case and the Americans in Kallonen and Sarjanen’s, do not immediately accept Törni’s surrender, but ask him to continue fighting the Soviet forces until they can evacuate the airfield. The story reflects National Socialist wishful thinking and the Cold War, not the setting of spring 1945. There is no reason to suppose that the Western Allied soldiers in May 1945 would have been ready to put their enemy ahead of their allies in this way.

(Juha Pohjonen & Oula Silvennoinen: Tuntematon Lauri Törni)

The 2017 one-volume-edition of Kallonen and Sarjanen’s work already contains several corrections from the earlier three-volume-edition, clearly inspired by Pohjonen and Silvennoinen’s criticism.

On 3 May 1945, Törni and his troops were surrounded by Russians near Hagenow airfield. Törni’s platoon once again fought their way out of the siege and came into contact with US paratroopers who held the airfield.

(Kari Kallonen & Petri Sarjanen: Lauri Törni 1919-1965)

It would appear that this episode has been wildly misunderstood until now. Yes, there had been an airfield, and yes, there had been US troops, and yes, British troops had eventually been involved. There might even have been „remnants of an unnamed artillery regiment“, that is, either men from Steiner’s Armeegruppe who travelled with Törni and Korpela or his company of sailors from Mürwik or soldiers from other, scattered units who had banded together for the journey. The elements are all there. But the reality is that, after fighting the Soviets at Pritzwalk, Törni and Korpela had simply tried to make their way home. However, „[after] walking for several days, they were captured by American paratroopers near Hagenaun [Hagenow] on 3 May.“ Given the fact that US forces had only occupied the general area on 2 May, and the airfield in particular either late in the evening of that day (as an Oberleutnant Bühler still managed to take off with his Fw 190 at 8:10 p.m., André Feit & Dieter Bechtold: Die letzte Front) or on 3 May, the camp at Hagenow airfield was likely still in the process of being set up. In fact, it might have been that very activity that Törni and Korpela stumbled into: The airfield was indeed „near Hagenow“.

There were barracks there already, but if the camp was indeed still being set up, it would make sense to hand the two Finns over to the British: There were other small camps in the vicinity of Hagenow.

[…] Törni and Korpela were taken into the custody of the British POW system. According to an interrogation report given by Törni to the Finnish State Police, they had been held in a prisoner-of-war camp of about 5,000 prisoners for two and a half weeks before being transferred to Lübeck.

(Pohjonen & Silvennoinen)

3 May 1945, it should be remembered, is the date Törni gives us. If Sarasalo is correct, it would be around 4 to 6 May. Steiner states that he became a British POW on 3 May. Joachim Schultz-Naumann in Mecklenburg 1945 writes:

Pritzwalk was reached [by the Soviets] on 2 May and the Red Army soldiers met with British Army soldiers at Grabow in Mecklenburg on 3 May.

So Törni, Korpela and Sarasalo would have been at Pritzwalk on 2 May, battling Soviet forces; Sarasalo was captured but escaped during the night, while Törni and Korpela either made their way northwest or straight west, skirting both the British forces at Grabow and the US forces at Ludwigslust. Even fit, lightly travelling soldiers like Törni and Korpela would probably not manage the 60 or so kilometres in a day on foot, and since Törni speaks of walking for „several days“, it is more likely they arrived at Hagenow airfield on 4 May.

Oh, and as to the Hagenau/Hagenow question („au“/“o“), it is pretty clear by this point that Törni never saw a sign spelling out the town’s name. I imagine the Finns or potential German companions asked their American captors where they were. „Hagenow,“ they answered, in the English pronounciation, thus creating confusion for decades to come.

Speaking of confusion: What happened to Felix Steiner? Did Törni, Korpela and Sarasalo meet him at Pritzwalk?

Well, it turns out that it wasn’t at Pritzwalk, but the meeting itself might just be a real possibility. Tucked away innocently inside Joachim Schultz-Naumann’s apparently vastly underrated book, there’s the answer to all the earlier discussions on military forums:

In the last days of April 1945, I was in the small town of Stolpe, not far from Ludwigslust.

General Steiner, in whose units I had participated in the Russian campaign, had fallen out of favour with Hitler. He was deprived of command of his troops. He was a free man, so to speak. An adjutant and two orderly officers were graciously left to him, one of whom was me.

The war was coming to an end with giant strides, and Steiner had only one goal, namely to achieve that the troops in the area north of Berlin could move into the territory of the Western powers shortly before the end of the war, so as not to remain on the Russian side under any circumstances.

How this could best be done was discussed in a hundred talks, but the implementation always seemed uncertain. The decision came sooner than expected. In our quarters in Stolpe we heard the news of Hitler’s death in Berlin on the night of 1 May. The way to a quick decision came the very next morning: we received a call from the commandant’s office in Ludwigslust, which suddenly ended with the words: I have to hang up now, the Americans are coming in. Steiner said to me, „So, now you have to do it. If I know anything about people, the commander, whether he’s a Yank or a Tommy, will take up quarters in your castle, that’s where you have to go.“

The writer of these lines was Friedrich Franz von Mecklenburg, the nominal heir apparent to the throne of Mecklenburg-Schwerin and Steiner’s adjutant.

Apart from me, two officers were sent there. At the entrance to the town of Ludwigslust, oversized white signs were set up on both sides of the road, white cloths, stretched square. We had to stop there, the belt and pistol were taken off, and after a short conversation we were loaded into a jeep and two cowboy-like figures drove us into the town. In the middle of town, near the Hotel Fürst Blücher, a lone American soldier in a worn camouflage suit, without a badge, was seen on the street. „That’s the general“ we were instructed, whereupon he got into another jeep and shouted, „Follow me to the Schloss.“

The arrival at the castle was impressive and unforgettable, for the steward and other employees of the house were standing in the doorway as if by chance, as they so often did to welcome my parents.

We went up to a room on the first floor [=second floor by US measuring], where you usually gathered with guests before dinner.

The conversation could begin. But the first words, in English on our side, were immediately interrupted harshly: „You speak German, not English, the interpreter is translating“.

So the unequal interlocutors were: on one side, three more or less minor German officers – and opposite, the victor, General James M. Gavin, commander of the 82nd Airborne Division in the Montgomery Army Section.

An attempt was now made to make the general understand what we actually wanted. The goal was a conversation between the commander of the 21st Army, General v. Tippelskirch, and General Gavin about the „insertion“ of the German troops behind the American lines. Of course, it had to be made clear: a surrender if necessary, yes, but at the same time, if possible, not to the Russians.

Gavin was initially extremely cool and insisted on the „unconditional surrender“, which we were of course aware of. But we gradually succeeded in getting his absolute agreement to the meeting with Tippelskirch.

It would appear Steiner’s part in the proceedings has been largely overlooked, to the point where he disappears completely from the records until his arrival at a British POW camp. Though von Mecklenburg states that the meeting between Tippelskirch and Gavin took place a few days later, Tippelskirch surrendered his army formally at 8 p.m. on 2 May (the day of von Mecklenburg’s meeting with Gavin).

General der Infanterie Kurt von Tippelskirch, commander of the Twenty-first Army, complied that afternoon, contacting General Gavin, commander of the 82d Airborne Division, in Ludwigslust. Tippelskirch surrendered his command unconditionally, though in deference to the Russians, Gavin specified that the capitulation was valid only for those troops who passed through Allied lines. […] The next day, 3 May, Tippelskirch himself entered an enclosure of the 82d Airborne Division along with some 140,000 other Germans of the Twenty-first Army […].

(http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-E-Last/USA-E-Last-19.html)

Of course, Steiner wasn’t left with just three officers, he still had the remnants of his ragtag Armeegruppe with him which, from von Mecklenburg’s account, he might or might not have surrendered as part of the 21st Army. Tippelskirch’s (and perhaps Steiner’s) men were interned in a hastily established camp on a field west of Ludwigslust. Now, there were several POW camps in the neighbouring villages; in fact, the entire region of Mecklenburg must have been dotted with those smaller (but daily growing) camps, and I’m not surprised the western Allies finally consolidated them in one huge assigned area in Holstein. (Mecklenburg fell under Soviet rule in summer 1945.)

But remember Steiner’s words about leading his men personally across the Elbe and Elde? Well, it turns out Dömitz is still not out of the running! An employee at the town archive of Ludwigslust who really went out of her way to help with my search for Felix Steiner dug up a source I hadn’t considered: The memoir of Christian Ludwig von Mecklenburg-Schwerin, younger brother of Friedrich Franz.

On the way back from the castle to the small village [Stolpe], he [Friedrich Franz] was captured by American soldiers. Therefore he did not take part in the surrender by General von Tippelskirch, which was signed the next day at my father’s desk in Ludwigslust Castle. He was sent to a prison camp near Dömitz on the Elbe and some time later to the far bank in British captivity […].

(Christian Ludwig Herzog zu Mecklenburg: Erzählungen aus meinem Leben)

So the negotiator was captured, but what about his boss?

Thanks to the phenomenal experts on Forum der Wehrmacht, I learned that the place of Steiner’s capture is named as „Golbosen“ in A. Stephan Hamilton’s The Oder Front 1945. Such a place does not exist. It is either Gorlosen south of Ludwigslust or Gorleben on the far side of the Elbe. The first option sounds more probable, both in name and in terms of travelling distance, while Gorleben is where many units who fought in the region and still managed to cross the Elbe at Lenzen ended up. But either way it had been a close call: The Red Army took Stolpe on 2 May, that is, the same day as von Mecklenburg’s meeting with Gavin and Tippelskirch’s surrender! (Wilhelm Tieke: Das Ende zwischen Oder und Elbe)*

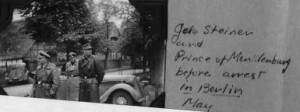

There is still the matter of the last photograph of Steiner and von Mecklenburg taken before their captivity (at least that’s what the caption says) that someone had posted on Forum der Wehrmacht. Try as I might, I was unable to pinpoint the street where it was taken (possibly it was redeveloped later), but I finally had success with the photographer. Dorothy Anne „Dottie“ Davis was a Red Cross helper attached to the 82nd Airborne Division and present when the 82nd liberated Wöbbelin concentration camp near Ludwigslust on 2 May 1945.

But after all that I’ve learned, the photo’s caption is completely wrong. The persons depicted appear to be correct, but I had already dismissed a whole chunk of the caption. It reads: „Gen. Steiner and Prince of Mecklenburg before arrest in Berlin May“, probably 1945, but the rest is cut off in the scan. Well, history tells us that Steiner wasn’t in Berlin in May ’45, and the buildings in the photo are clearly not Berlin houses. So it might be Stolpe, if Hamilton’s source is incorrect and von Mecklenburg led his captors to his superior officer. Or it might be Wöbbelin, where Steiner and von Mecklenburg were reunited after their individual capture. The civilian population was ordered to tour the concentration camp after its liberation, and some sources mention that captured German officers were made to do the same. So why not Steiner and von Mecklenburg? It would absolutely make sense: The dead from the concentration camp were buried on the lawn of Ludwigslust Castle where they still rest today, in a very public place. To have von Mecklenburg as both a member of the ducal family in whose neighbourhood the camp was set up as well as a member of the German armed forces (his family actually disinherited him because of his Nazi ties) and Felix Steiner as a Waffen-SS general see the atrocities perpetrated by the regime they, as military men, had upheld, seems exactly the sort of thing Gavin would have ordered. It would also explain Dottie Davis‘ presence. That would mean that the picture was taken after Steiner’s and von Mecklenburg’s capture but before their long-term internment.**

From all this, it becomes clear that Steiner wasn’t anywhere near Pritzwalk at the beginning of May 1945. Did Törni and his companions actually meet him? It is possible. As Steiner had established his headquarters at Stolpe in the last days of April, they might have learned of it and gone there. But it would appear, although Steiner offered to keep them as guards at HQ, if Sarasalo is to be believed, they were still eager to see some action. They moved on south-eastwards, meeting the advancing Red Army near Pritzwalk on 2 May.

Now, there is almost no information on the fighting itself. For various reasons, as I see it, hardly anybody has bothered to tell the story of the day when the Red Army marched into Pritzwalk. There is one long out-of-print publication by Kurt Schein, Und dann war kein Krieg mehr: Das Ende in Pritzwalk, that I cannot get my hands on, which may or may not include some helpful hints. But Forum der Wehrmacht came to the rescue again with a mix of local knowledge and family history.

In the first days of May, parts of the 4th SS Police Division drove with armoured reconnaissance vehicles through Pritzwalk in the direction of Wittenberge. In addition, of course, there were huge numbers of scattered Wehrmacht units.

The bulk of the Russian assault groups came from Berlin via Kyritz and moved in the direction of Wittenberge in order to cut off the escaping Wehrmacht units from the Elbe.Here they stayed on the main roads with tank spearheads and refrained from a broad approach. A coherent resistance was actually no longer expected. In Kyritz, a bridge was blown up to stop the Russian tanks. At a water level of 50-75 cm, they simply drove through the river next to the bridge.

From the Trappenberg near Pritzwalk, the first Russian spearheads coming from Kyritz were fired upon with a machine gun before an immediate retreat.

Very heavy fighting took place in the Wittenberge area. Here, especially the still more or less intact SS units offered stiff resistance to secure the crossing to the other side. The ammunition finds in the Prignitz, which are still abundant today, clearly show that here they only relieved themselves of all ballast in order to retreat more quickly.At the same time Russian tank spearheads were approaching Pritzwalk from the direction of Wittstock. The SS police units came from the same direction some distance ahead.

At the monastery of Heiligengrabe there was a fierce battle between SS and Russian tank units. As a result, the monastery library went up in flames.An old army road ran from Wittstock via Heiligengrabe, Wilmersdorf, Alt Krüssow, Beveringen, Kemnitz to Pritzwalk. However, this was only a better service road. Relying on old maps, the Russian tanks marched in single file along this army road. This gave the SS units a good and safe lead, since they used the better country roads.

In anticipation of the Russian invasion, white flags had already been hung in my grandparents‘ village of Alt Krüssow. The SS police units took this as an opportunity to make a brief stop. The commanding officer went to the villagers and angrily said, „Take down the flags, the Russians aren’t here yet.“ Shortly afterwards, however, they were gone again.

In the evening, probably around 7 p.m. on 2 May, the Russian T-34s came into the village via the Heerestraße. In the evening at 8 p.m., the tanks rolled over the provisional tank barriers in Pritzwalk.

(https://www.forum-der-wehrmacht.de/index.php?thread/10198-elb%C3%BCberg%C3%A4nge-april-mai-1945/&pageNo=2)

This, without doubt, is the fighting that Törni, Korpela and Sarasalo were involved in. And here, perhaps, is finally the explanation of the Steiner mystery: The 4th SS Police Division had been part of the 11th Panzer Army commanded by Steiner, and parts of it were probably then attached to Steiner’s Armeegruppe. It would appear the three Finns indeed succeeded at meeting „Steiner’s troops“, not Steiner himself, „at a road junction“ and joined up with them. One unit of the 4th that has been explicitly named to have fought at Pritzwalk is the Schirmer Brigade; and while division headquarters of the 4th was in Kleinow at the time, maybe Schirmer had an HQ of some sort to which Törni and his companions were assigned, and the whole story about Steiner was just a result of poor language skills and misunderstanding. It would certainly fit with both Törni’s and Sarasalo’s account that the fighting near Pritzwalk took place very shortly after they were being assigned to HQ guard.

The front had suddenly moved under Russian pressure and [Törni] and Korpela had decided to leave the vicinity of the front, but at [Pritzwalk] they had come into combat with Russian troops and the latter had broken through the German front, but [Törni] and his comrade had managed to escape through the woods.

Törni and Korpela, but most of all the captured Sarasalo were actually very lucky, as evidenced by Sarasalo’s own account („Sarasalo watched as a Russian officer demanded that a German sergeant tear off his SS emblems. The German refused, and he along with 20 other German soldiers were pulled aside and machine-gunned“) and by the user on Forum der Wehrmacht:

Until the fall of communism, many individual graves of German soldiers were found in the woods between Pritzwalk and Wittstock. Prisoners were probably not taken in the last phase and every soldier was shot on the spot.

In the past few years, the soldiers have been reburied.One of these young soldiers who was shot was a 17-year-old who had wandered into the village after becoming separated from his unit. The inhabitants wanted to hide him, but he wanted to return to his homeland of Saxony. He went into the forest and tried to pull a bicycle off one of the Russian trucks that had been piled up there en masse. He didn’t get far. As far as we know, they used him for target practice.

Those soldiers of the 4th SS Police Division who managed to surrender to the Western Allies did so at Ludwigslust and at the American bridgehead at Lenzen… again bringing to mind Steiner’s words about leading „his troops“ across Elde and Elbe. Lenzen, after all, was the gateway to Gorleben, one of the two possible places of Steiner’s capture.

Addendum 3 July 2022: A regional researcher contacted me after reading the blog series with some corrections:

* „Stolpe was not taken/occupied by the Russians on 2 May, but around midday on 3 May. […] The command staff of the 21st Army moved from Stolpe to the Neustadt-Glewe airfield in the night of 3 May in order to give the swelling retreat (consequence of the Tippelskirch – Gavin negotiation of the previous evening) something like a little order from there. (personal notes Tippelskirch, 1949) When the Russian tanks appeared in Stolpe-Blievenstorf around noon (not T-34s, by the way, but M4-A3 ‚Shermans‘ from US deliveries), the entire staff motorised to Ludwigslust and thus became prisoners of war of the 82nd Airborne Division.“

** „Regarding the photo in question: It comes from Dorothy („Dottie“) A. Davis’s private album. The copied pages are in the archive of the Wöbbelin concentration camp memorial museum. I have been able to view this album. And I strongly doubt that the photographer of this photo was D.D.! (There are other photos in it that the woman could not have taken herself). The partly „wrong“ caption also suggests that the album was only created in the USA after the end of the war. The photo does show Obergruppenführer Steiner and Friedrich Franz on a tree-lined street with village buildings, but it also shows a third person in uniform (Waffen-SS). The whole scene does not look as if US soldiers were already present. Besides: the trees are conspicuously lush with foliage! Quite advanced for the beginning of May. […] A word about the person of D.D.: As a „Red Cross helper“ of the US Army, she was not active in the medical service. In this respect, as a member of a kind of rear service, she did not take part in the „liberation“ of the Wöbbelin subcamp, she visited it days later. Her colleague Violet A. Kochendoerfer, who was (also) in Ludwigslust together with her, temporarily assigned to the 82nd Airborne Division, described the activities, a kind of „troop support“, in detail in her memoirs „One Woman’s World War II“, copyright 1994, The University Press of Kentucky. (exaggerated: setting up clubs, baking donuts, party escort, sightseeing). […]

Even if it is carved in stone and by now also cast in bronze, and is constantly repeated verbally and in writing: It was not the soldiers of the 82nd Airborne Division who discovered and liberated the camp (the gates were already open, the guards had long since fled), but verifiably medical soldiers of the 8th Medical Battalion / 8th US Infantry Division under the regimental surgeon Captain Francis A. Dry. In addition, on 4 May, jurisdiction / responsibility for the camp was transferred to the 28th Infantry Regiment / 8th Infantry Division. It was these units that initiated the first relief and assistance measures! […] That today the main credit for the liberation of the Neuengamme subcamp is attributed to the 82nd Airborne is, according to my research/evaluation, a result of clever propaganda.“

The Lauri Törni in Germany 1945 series:

Outtake: Riikka Ojanperä, and a visit from the beyond

More Törni-related blog content:

„Alles, was ich getan habe, geschah zum Wohle meines Landes.“