She introduced me the two men – and a third one, who was standing in the background, and whom I had not noticed [- „] Longin B. – we call him ‚Leo‘ – former Oberscharführer S.S., released from Werl along with me, ten days ago: Heinz G. another S.S. comrade, released from Werl last year; Erich X., for long years a prisoner of the Russians.“ […]

The three men shook hands with us. Leo B., the tall one(1) whom Anni had seen from the railway carriage, patted me on the shoulder and said, with a happy smile: „I am very, very glad to meet you at last; Hertha has told us all such a lot about you!“ […]

An auto was waiting for us. Erich, who was to drive, sat in front. The two S.S. men tried to squeeze themselves at his side, but could not: Leo B., being nearly six feet tall, was big in proportion; and Heinz was not thin. We laughed.

„Come!“ cried at last Hertha to Leo. „Let Heinz sit at the back with us. Can’t you see you need the whole place to yourself?“

„As though four can sit at the back when you are one of them, you fatty,“ retorted he. „And Heinz is hardly smaller than I; and Anni…“

„Muki is the feather-weight among us; I’ll take her on my lap,“ answered Hertha. […]

„I am not as well as I look,“ replied Hertha; „my nerves are in a bad state, the doctor says. And what appears at first to be „fat“ in my body is nothing but water-swelling; the result of eight years of prison diet.“

„Still, you are at last free,“ said I. „It is a joy to see you free, and as firm as ever in our glorious National Socialist faith.“

„Firmer and more uncompromising than ever! Ready to begin again and avenge our dead comrades, and repay those swine for all that we have suffered,“ said Leo, turning around and squeezing my hand in a sign of warm approval. […]

I wished to embrace all five of them, – and, beyond them, the whole heroic legion of my brothers in faith – and, smiling to them, I intoned the Song of the S.S. men; the triumphant hymn that had sprang from the wagons of death in 1945, defying the forces of darkness: Wenn alle untreu werden, so bleiben wir doch [treu]…

The others joined me. Leo turned around and, for a second, looked at me with a beaming face, while continuing to sing.

(Savitri Devi: Pilgrimage)

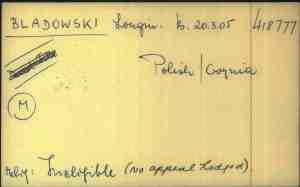

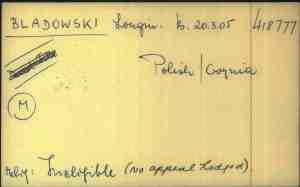

With a first name like that (we’ll return to it later), it was ridiculously easy to find out who „Longin B.“ was. I just typed it into the name search of the Bundesarchiv database, and presto.

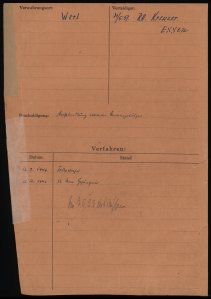

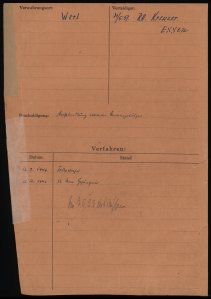

Subject of the application/proceedings: Maltreatment of allied nationals in KL Neuengamme and other places, 1939-1945 […]

Sentence: Death sentence, commuted to 12 years imprisonment, released in 1953(2)

A somewhat outdated Wikipedia entry tells us (my translation):

It is not known how many of the women from Salzgitter-Bad lived to see the end of the war. The camp commanders were SS-Obersturmführer Peter Wiehage and, from the end of 1944, SS-Untersturmführer Longin Bladowski. Bladowski was later sentenced to twelve years in prison. It is not known how long he was imprisoned.

Longin „Leo“ Bladowski is such a colourful character in Savitri Devi’s Pilgrimage that I knew I would do further research into his life one day. Well, here we are. It turns out that there is a surprising amount of information available on the internet, most of it drawn from Bundesarchiv files and most of it centered around his time as SS personnel in the concentration camp Neuengamme and its subcamps; which is where his death sentence came from.

SS man Bladowski came to the potato peeling kitchen. We were 60 comrades, all sick and physically disabled prisoner [sic].

He forced us to work 36 hours without sleep in November 1944, December 1944 and many prisoners collapsed.

Bladowski is fully responsible for his orders.

The foreman Teddi Ahrens was often with him and made him aware of the prisoners‘ difficult situation, but he took no notice of this.

Bladowski beat the sick prisoner [sic] if he caught them taking potato [sic] to the barracks.

(Rudolf Esser, 1.3.1946)(3)

Albin Lüdke, a former prisoner of Neuengamme concentration camp, visited the internment camp on the site of the former concentration camp together with a British investigator on 5 March 1946. The purpose of the visit was to prepare for the military trial against members of the Neuengamme concentration camp management that was to begin shortly afterwards, in which Albin Lüdke was to testify as one of the main witnesses for the prosecution.

My impressions of the camp were as follows: The appearance of today’s inmates is an exceedingly good one, indeed, I would like to say […] some people I know personally, e.g. SS-Oberscharführer [Longin] Bladowski, Untersturmführer Ludw[ig] Rehn, SS-Oberscharführer Albert Letz, look physically better and healthier today than they used to. The pace of movement is slow. I could not find any labour detachments, only those that corresponded to camp maintenance (kitchen staff […] etc.) […]

In the [former] rooms of the labour detachment […] Captain Freud had meanwhile made some small interrogations about the charge […]. […] Untersturmführer Rehn could […] not remember […] having beaten the guards with a riding whip in 1942 when the labour detachments were deployed to the roll call area. Similarly, Oberscharführer Bladowski, whom the indictment accuses of [throwing] prisoners into the water basins used for washing vegetables and potatoes, could no longer remember this.(4)

A bit on Albin Lüdke (1907-1974) for context (my translation):

Lüdke, who was born near Poznan, worked as a painter in Düsseldorf, where he was active in the KPD [Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands = Communist Party of Germany] in the 1930s. After seizing power, the National Socialists accused him of continuing the banned Red Aid of Germany and imprisoned him in Börgermoor concentration camp for this reason in June 1933. His imprisonment ended on 22 December 1933, and shortly afterwards he distributed a leaflet entitled „Save the 10 Gerresheim workers“, who were to be executed after bloody disputes with the SA. For this reason, Lüdke was imprisoned again on 20 January 1934. The Hamm Higher Regional Court judged the distribution of the notes to be „preparation for high treason“ and sentenced Lüdke to fifteen months in prison. His prison term in Remscheid-Lüttringhausen ended on 21 April 1935 and he was arrested again on 2 July 1935. Lüdke spent four weeks in police custody and was then transferred to the Esterwegen concentration camp. As the judiciary was to take over the concentration camp, Lüdke and all his fellow prisoners were transferred to Sachsenhausen concentration camp on 1 September 1936. As he was considered a „political recidivist“, Lüdke was given a place in „isolation“. In these barracks, which were separated from the camp, there were numerous communists who were repeatedly mistreated by the SS. The Jehovah’s Witnesses, of whom he was the block elder, showed him great respect, as although he did not share their beliefs, he accepted them.

After almost four years in Sachsenhausen, Lüdke was transferred to Neuengamme concentration camp on 4 June 1940. As a member of the painters‘ column, he was appointed foreman eight weeks later and later Kapo. Even though he could have beaten his fellow prisoners, he did not make use of it and did not take advantage of them. Fellow prisoners said after the end of the war that he always acted calmly and prudently, even under pressure from the SS. In January 1943, Lüdke was promoted to „Arbeitseinsatzkapo“. In the SS leader’s office, he organised the prisoners‘ work and manipulated transport lists so that inmates whose lives were in danger were transferred to subcamps. Shortly before the end of the Second World War, Lüdke was assigned to the Dirlewanger SS special unit. He went with this unit to the SS barracks in Hamburg-Langenhorn on 29 April 1945. He was able to escape a few days later.

Immediately after the end of the war, Lüdke prepared trials against concentration camp guards together with the British occupying forces. In the courtyard of the court prison in Altona, he named the camp guards during confrontations. From 18 March to 3 May 1946, he was the first witness to testify at the Neuengamme main trial. On three trial days, he described the organisation of the concentration camp, made statements on the ten most important charges and the personalities of the 14 defendants. During an on-site visit, he explained the concentration camp site to the judiciary.

Lüdke later lived in Hamburg, where he opened a small painting business. As a staunch communist, he was committed to the KPD and received a three-month suspended prison sentence for illegal activities for the party after it was banned in 1956. On 6 July 1948, he co-founded the Neuengamme working group and served as the association’s first chairman until his death in March 1974.(5)

(https://collections.arolsen-archives.org/de/document/66618963)

(https://collections.arolsen-archives.org/de/document/66618963)

Here I want to insert something that doesn’t properly belong in a biographical article, but I find it important to point out, especially in an article about a highly emotionally charged topic like concentration camps where in our current narrative the inmates are always the innocent victims and the guards are always the guys you know from Hollywood. The former can and must be believed in everything they say, the latter cannot and must not. Now, did abuse happen? Absolutely. But things are seldom as black and white as we are led to believe.

We always have to maintain a healthy scepticism about any source. The people behind any statement are not neutral bystanders – not me, not you, not Savitri Devi, and not Albin Lüdke. In German, we call it Quellenkritik, source criticism, and after more than twelve years of biographical research I am its most ardent proponent. Too many authors and researchers neglect that crucial part of their work, I have learned, either out of laziness or because of emotions (that includes political and ideological beliefs). Always double-check. Triple-check. Who is making the statement, and what is his or her background? What is their motivation? Do they have a bone to pick or advantages to gain? Are they simply mistaken? Do they mistake rumours they heard for actual facts? Were they pressured into making statement X? How does a statistic come about? What are the sources for it, who compiled it, and how? And so on, and so on.

So when I read a statement like „The appearance of today’s inmates is an exceedingly good one, indeed, […] Bladowski, Untersturmführer Ludw[ig] Rehn, SS-Oberscharführer Albert Letz, look physically better and healthier today than they used to. […] I could not find any labour detachments, only those that corresponded to camp maintenance“, my alarm goes off. It might be that Lüdke is correct and simply being nasty, or it might be that he is lying and trying to score points with the British (and the rest of the Allies) for suggesting how well they treat their prisoners, those undeserving, dastardly Nazis. I’ve read too many shitty, cynical, and downright evil lies of that kind over the years to believe any of it without a second, third, or fourth opinion. Always be sceptical. People lie, sometimes in the most outrageous and brazen fashion.

That is the reason why I often, in these biographical sketches, simply quote the sources. Here is what witness XY says; make of it what you will. I will add context or corrections or my own speculations, but I aim to do what Carol Bowman wrote about Dr. Ian Stevenson: „I saw that he is, first and foremost, an empirist. His mission is to gather data and publish it unadorned for others to examine; he assiduously avoids drawing conclusions or making claims.“(6)

You may not like what you find once you start digging. It may even hurt. I’ve experienced this more than once. But like I’ve said elsewhere, learn to accept it, whatever you find. The truth will set you free.

All that being said, the document featuring the Lüdke quote, Ehemaliges KZ-Personal im Internierungslager Neuengamme, shows a photo of the inmates in the Allied-run Neuengamme camp. It is not dated but must be from about 1945/46, and no, they do not look like they were being ill-treated. It doesn’t mean they weren’t; it means the men in the picture do not look like it. Always question photos, too. However, the British were, according to all sources (see?), known to treat their German prisoners the most humane of all four occupation forces. Did abuse happen? Absolutely. But that seems, sadly, to be part and parcel of all prisons and all camps.

Overworking prisoners and throwing them into water tubs (I doubt the „throwing“ part; let’s be real. He wasn’t the Hulk(7)) was not all Leo Bladowski was up to:

The SS Fahrbereitschaft looked after several cars and lorries as well as a bus. At the end, the SS Fahrbereitschaft had twelve vehicles at its disposal, including the Mercedes-Benz convertible of commander Max Pauly. The vehicles were used to pick up food and drive it to the kitchen, take corpses away and transport SS men to places of deployment. In the final weeks of the war, these vehicles were used to transport food, paintings, furniture and other furnishings from the SS camp to Wesselbuhren/Dithmarschen, Max Pauly’s home town, and to Süderbrarup in the district of Schleswig to the farm of kitchen boss Longin Bladowski.(8)

By the way, the document Besoldung of the Neuengamme memorial site uses the case of Longin Bladowski to document income and benefits of SS men.(9) It lists Bladowski as Unterscharführer (NCO) in October 1943, which confuses matters just a bit more: Wikipedia claims his rank was Untersturmführer (second lieutenant); Savitri Devi and Albin Lüdke name him Oberscharführer (sergeant). An application form clears it up for us: Bladowski was made an Unterscharführer in May 1942 and an Oberscharführer in May 1944. So once again, Wikipedia is dead wrong.

Longin Bladowski, born on 20 March 1905 in Rahmel (Poland). Agricultural school; two years‘ service in the Polish army; trained as a ship’s machinist; married in 1932, three children; 13th SS Totenkopfstandarte in Linz/Austria in 1940, where he worked as a signalman and telephone operator. 1940 guard at Buchenwald concentration camp; 1942 SS assistant cook at Neuengamme concentration camp, 1943 SS chef; 1944 transferred to Salzgitter-Drütte subcamp. Bladowski mistreated prisoners and was involved in food racketeering and theft.(10)

The latter is quite likely true. It’s the same in the reports of almost all camps, whether Germans ran them or were imprisoned in them. If you were in charge of the kitchen, you had a high chance of being corrupt. It’s a sad fact. Kitchen duty was also a highly coveted job among the inmates, for obvious reasons, and the kitchen supervisor and his „staff“ often formed a tightly knit group. This was also the case with Bladowski and his men, as we will see later.

But who was Leo Bladowski, to start with? He was, as quoted above, born in Rahmel, today’s Rumia, that is, in the former German eastern provinces that were given to the re-established Polish state after the First (and Second) World War. So Bladowski was a Volksdeutscher, an ethnic German living in a foreign country. His father’s name was Michael(11), and he was an Amtsdiener, that is, a municipal employee; though he appears to have come from a family of musicians! According to Longin Bladowski’s own testimony, his mother’s name was Ida, née Schenk-Wittbrot (if I read his old German cursive correctly; the latter half of the name is more commonly written with a dt, „Wittbrodt“)(11), though his birth certificate simply gives her maiden name as Schenk. Ida’s death certificate, on the other hand, gives her mother’s maiden name as „Weichbrodt“. Ida died on 26 October 1918, and young Longin was the one to inform the Standesamt of it. Why? The certificate tells us that Ida, at the time of her death, was already widowed. It gets worse: Four pages up in the death registry, we find Michael Bladowski’s entry. He had died on 21 October 1918, and a midwife by the name of Monika Schenk (née Weichbrodt, so clearly a relative) reported his death. So there was young Longinus Joseph Bladowski, an orphan at age 13, having lost both parents in the span of a few days.

He had seven siblings, according to Bundesarchiv file R 9361-III/252982. Generally, the family was extensive in the Rahmel area. Right next to Longin’s birth certificate, there is that of a Helmut Anton Bladowski, born just six days earlier, to Jakob and Martha Bladowski, and the surname appears again and again in the Standesamt records. In the Volksbund database, there is an Eugen Bladowski of Rahmel who died on 4 June 1918 at Jena. The death certificate reveals that he was one of Longin’s brothers. He had been 18 years and three months old and had volunteered as a male nurse. Other siblings included (I missed one) Bruno Michael (*1902), Magdalene Ida Margarethe Helene (*1903), Georg Anton (*1906), Erwin Otto (*1907) and Ida Erika Eleonore (*1910).

Longin served in the Polish army and trained and later worked as a ship’s machinist, which is not surprising given Rumia’s proximity to the sea and to the port cities of Gdynia (Gotenhafen) and Gdansk (Danzig).

The fact that he went to agricultural school is also interesting. Remember he was supposed to own a farm in Süderbrarup in 1945 – but I was sceptical about that claim when I first read it. How and why would Bladowski have bought a farm in Schleswig-Holstein? It might have been just a farm he had access to via acquaintances. And indeed, in a document I discovered later we find the following statement:

My group included Sievers, the former kitchen boss Wendefeuer and the head of the prisoners‘ kitchen Bladowski. We had loaded paintings and fur coats, among other things. The main transport with Pauly went to his home town of Wesselburen. Bladowski’s deputy as kitchen boss, who had a farm and a cattle business in Süderbrarup, wanted to take us in.

On the way a dispatch driver had given us the order that we were also to go to Wesselburen. Our guide, the former Spieß [sergeant] (in the camp commandant’s office) Werner (I can’t remember his surname), took it upon himself not to obey the order. […]

At the time of the surrender (8 May 1945) we were in Süderbrarup. From Süderbrarup we drove back to Hamburg in the same lorry through occupied Schleswig-Holstein. We had taken off our licence plates and the rank insignia from our uniforms. We managed to get into Hamburg with a forged document – I’ll tell it like it is. There Sievers, whose father’s soap wholesale business we stopped at, gave us civilian clothes.

I wanted to go to Grabow. Together with Bladowski, I marched to Neuengamme, where we stayed for a few days.(12)

In February 1940, Bladowski was serving in a Nachrichten-Truppe, a message unit, which makes sense given the fact that he was almost 35 years old at the time, practically an old man in soldiers‘ terms. (My grandfather was drafted in 1942 when he was 34 years old.) As to his physiognomy: He is described as being slender, with a „comfortable“ posture, a roundish skull and prominent cheekbones, greying hair and blue eyes.(13)

Bladowski and his wife had three children, Richard, born in 1937 (died in 2022), Gisela, born in 1940, and Jürgen, born in 1943. Interestingly, in Bladowski’s application for emergency funds after Jürgen’s birth, he lists a bank in Gotenhafen, which was supposedly his workplace residence – but how does that make sense if he was stationed in Neuengamme (Hamburg)? His bank changed on 1 May 1945 (interesting date, and interesting that they even still documented it) to one in Altenwalde/Cuxhaven. So it would appear as though Bladowski continued to live in the Gdynia area until the end of the war, which might explain why he went with eyewitness Wilhelm Möller – as quoted above – in the general direction of Grabow, that is, east.

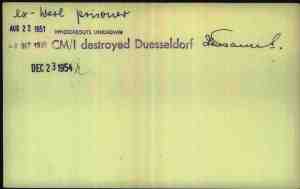

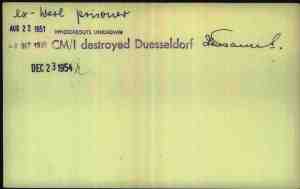

(Am I the only one to think „Whereabouts unknown“ after the stamp Aug 22 1951 is funny? Did they lose him in Werl, or what?)

(Am I the only one to think „Whereabouts unknown“ after the stamp Aug 22 1951 is funny? Did they lose him in Werl, or what?)

„Now, tell me how things stand in Werl; how many more of us are still there?“ asked I.

„Ninety-seven men, to my knowledge,“ replied Leo. […]

„Those bastards would now like to have us on their side,“ put in Heinz. „But I am afraid it is too late; they have missed the bus.“

„Let them first release all those of us whom they still detain behind bars,“ said Leo. „In the male section in Werl, there are, as I told you, ninety-seven of us still waiting to come out – and great ones, such as General Meyer; you know: ‚Panzer-Meyer.‘ .. And how many more in Wittlich, and in Landsberg, let alone in the prisons of France and Holland and other countries of the so-called ‚free‘ world, which we are now invited to defend ‚against Bolshevism‘?“

(Savitri Devi: Pilgrimage)

A short notice in the Revue de droit international, de sciences diplomatiques, politiques, et sociales (International Law Review), Vol. 31 (1953), announced the release both of Longin Bladowski and Hertha Ehlert from Werl, along with Albert Letz, who had been tried with Bladowski eight years previously (my translation):

The British High Commission announces the release of three war criminals from Werl prison on expiry of their sentences. They are LONGIN BLADOWSKI, aged 48, ALBERT LETZ, aged 55, HERTHA EHLERT, aged 48, sentenced to various terms of imprisonment for the abuse of allied nationals in the Bergen-Belsen and Neuengamme concentration camps.(14)

Hertha Ehlert was released on 7 May 1953, according to Wikipedia. She and Leo Bladowski were then sent to the Fischerhof convalescence home near Uelzen, where Savitri Devi met them and several other National Socialists.

I can never forget Hertha’s introductions: „Hans F., Sturmführer S.S., just released from Landsberg; Lydia V., sentenced to death by the French, and now just released from Fresnes; Leo B., sentenced to death by the British, and released from Werl at the same time as I, i.e., on Thursday before last; Anni H., one of us in the Belsen Trial, released from Werl in 1951; our ‚Muki,‘ released from Werl three years ago, author of Gold in the Furnace and Defiance – our story – and… you know me, Hertha E., former overseer in Belsen…“

„[…] And what I love, what I worship in the Third Reich, is the fact that it has at last brought forth an élite – the S.S., – who also stood up against them in the name of the natural, eternal values of Blood and Soil, and of Aryan pride. Glory to the S.S., early vanguard of that regenerative Aryandom of my dreams! May I, one day, see its surviving veterans seize power and rule the earth!“

„Our ‚Muki‘! It is a joy to hear you speak, ten days after one’s release,“ said Leo, putting his strong hand upon my shoulder in a gesture of comradeship, and gazing at me with a happy smile.

(Savitri Devi: Pilgrimage)

It was at the Fischerhof that doctors first recognized and studied PTSD in former prisoners of war. In 1952, head doctor Kurt Gauger published a report, Die Dystrophie als psychosomatisches Krankheitsbild (Dystrophy as a psychosomatic condition), in which he argued that dystrophy, a common condition in prisoners of war, especially those held in the Soviet Union, was not only a physical but also a psychological phenomenon that came with unusual symptoms such as nightmares, fear of being pursued, nervous reactions to passing trains or to smells, inexplicable exhaustion, sudden bouts of violence. It was so common in post-war Germany, not only in former POWs but also civilians, that the theory of heredity as the main cause of dystrophy simply didn’t hold water. Gauger was on the right track, of course; only it wasn’t dystrophy that caused these symptoms but Post-traumatic stress disorder. It had been known as shell-shock after the First World War, but studies only focused on former combat soldiers. Only in later years became it known that the causes and effects were much broader.

I sat at the table [with] Hans-Georg P., Herr K., (whom I had met during my first visit to Fischerhof), Edith – Hertha’s roommate; a girl of twenty-three, recently released from a Russian slave-labour camp where she had spent eight years – Lydia, all greeted me again. But I could not see Leo. „Where is he?“ enquired I.

„Upstairs, in his room, brooding,“ answered Hans F. sternly. „He has had a good ‚telling off‘ from me, and is not to sit with us…“

„Oh, why?“ asked I, sincerely grieved at the tone of our comrade’s voice, no less than at the fact that Leo – whom I admired – had been put en quarantaine. „Poor Leo! What has he done?“

„He can’t behave himself,“ explained Hans F. „He can’t keep his paws off the women… People complain. And it creates a very nasty impression here, upon those patients who are not of our faith. They all know who he is, naturally. And they say: ‚Those Nazis! Look at them!‘ as though we all are a pack of he-goats, the lot of us. It is a disgrace.“

„Poor Leo!“ repeated I. „Can’t you forgive him? After all, he has been for eight years confined to a prison cell. And he is ideologically irreproachable – as faithful and devoted to the Cause as the best of us can be. Personally, I could not care less what he might do or try to do with women, provided he remains a perfect National Socialist. And as for people who take pretext of silly incidents of such a nature to criticise us, well… they will criticise us anyhow, whatever we do. Tell them to go to hell!“ I felt full of sympathy for the handsome S.S. man’s all-too-human weakness, and was rather amused at the importance which Hans F. (and Hertha herself, by no means a prudish woman) seemed to attach to it.

But Hans F. tried to make his point clear to me. „I don’t mind their reproaching us with our ruthlessness,“ said he, speaking of our opponents. „Ruthlessness is a virtue. But I am not having anyone reproach us with lack of self-discipline. This man was eight years in Werl, you say. Well, I was eight years in Landsberg. We all suffered. That is no excuse for losing our dignity. A National Socialist – and specially an S.S. man – should be master of himself.“

(Savitri Devi: Pilgrimage)

Some time after his release, Bladowski moved to Hamburg. The first entry that probably pertains to our Longin B. is in the address book of 1955. I say probably because his first name is given as „Lopien“. I was immediately reminded of the talk I had had with my mother literally hours earlier when I had asked her, mainly as a joke, if she had had a neighbour called Longin Bladowski during her time in Hamburg (which was roughly around the same time he lived there). Her reply? „That can only have been a foreigner!“ I then spent some time explaining to her that, no, Longin was actually a very Catholic name. But apparently, someone in 1954 or 1955 had felt the same way as my mother and couldn’t make sense of the name. All the other data fits, so I’m confident we’re dealing with the same person here. His profession is given as „Masch.“, which stands for „Maschinist“, machinist. Given the fact that Bladowski had trained as a ship’s machinist and that Hamburg is a port city, his post-war, post-prison profession makes complete sense. The subsequent editions of the address book show him as L. or Longin, the only Bladowski to be listed; he lived first at Eppendorfer Weg 12 (1955), then at Goebenstraße 22 (1956-1960 or so – there is no entry in the editions of 1961 and 1962), and lastly at Fibigerstraße 378 (1963-1966).

In 1967, the entry suddenly changes. There is still only one Bladowski, but her name is Ursula. This continues in subsequent editions of the telephone book. So if I had to guess, I’d say Ursula was Longin’s widow, meaning that he died in his early 60s. I’d further suspect „Ursula“ was Ursula Lemke, who, according to the few existing sources on the concentration subcamp Salzgitter-Bad, had been engaged to Longin Bladowski when he was supervisor there.

In 1949, Ursula Lemke was arrested on suspicion of mistreating prisoners. She arrived at the end of September 1944 in the camp as an SS overseer. She had undergone a six-day training course in Neuengamme. She remained at Salzgitter-Bad until the camp was evacuated. When questioned, she stated that she was engaged to the Lagerführer (camp leader[; actually „Kommandoführer“ in the book the English text was translated from]) of the Salzgitter-Bad camp, Longin Bladowski. Bladowski returned to the main camp [Neuengamme] before the end of the war, where he took charge of the prisoners‘ kitchen.(15)

Ursula Lemke was not tried for want of evidence.(16)

What that means, I thought to myself, is that Longin Bladowski either got divorced, or his first wife died soon after the birth of their third child. I wondered if either possibility was what he referred to when he told Savitri that he was ready to fight again, „not in order to regain what I have lost (there are things one cannot regain)“.

However, given Bladowski’s eye for the ladies, there was a third option: What if he had simply lied to Miss Lemke? Which isn’t that uncommon even today. „Of course I’ll leave my wife and kids for you, honey!“

It was at this stage that I got Longin Bladowski’s file from the Bundesarchiv Koblenz. After pages upon pages of bills by Bladowski’s lawyer to the state of Germany and the state’s request for documentation, and correspondence between the two going back and forth, things got very interesting – and his words to Savitri suddenly made a lot of terrible sense.

The file is in essence a documentation of two person’s fight to free Longin Bladowski from prison: His lawyer, Marianne Kreuzer(17), and a Dutch journalist by the name of Albert van de Poel who had been an inmate in Neuengamme. Van de Poel’s granddaughter, Geertrui van den Brink, published a book about him in 2018. In it, she mistakenly refers to Bladowski as having been a Kapo (that is, a prisoner in a position of authority) and a Pole. The latter is an understandable error, and Ms van den Brink is not the only one to have made it, as we will see later. The former probably stems from the fact that Bladowski was in charge of the prisoners‘ kitchen; if you’re not familiar with the command structure in Neuengamme camp, it’s easy to draw the wrong conclusion. Van de Poel worked in the kitchen and got to know Bladowski there.

I learned from the file that Bladowski had had his death sentence commuted to twelve years in prison only three months after his trial, which really surprised me. 1946 was the year of the Nuremberg trials, meaning that the Neuengamme trial took place in an atmosphere of absolute revanchism. It was vicious. Hundreds of people were hanged. Therefore, I was not surprised at all that Bladowski had been sentenced to death; but something must have happened to make the authorities rethink their decision in his case.

If we examine the statements both of Bladowski’s lawyer and Bladowski himself in the early 1950s, we might not learn what that something was, but we do learn that his trial, like many others, was rigged. And that, ironically, might just be what led to his pardon later on.

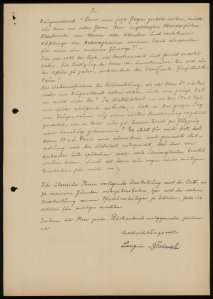

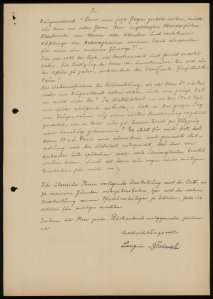

On 3 March 1951, Bladowski wrote (in his beautiful handwriting) from Werl prison to the legal protection centre for prisoners of war (Rechtsschutzstelle für Kriegsgefangene) in Bonn:

I was sentenced to death by a British military court in Hamburg on 13 July 46. On 26.X.46 this sentence was commuted to 12 years imprisonment. The conviction was for alleged maltreatment of All. nationals.

In the following I take the liberty of submitting to you an account of the trial.

I was drafted into the Waffen-SS in Prague on 11 November 1939. Around the beginning of 1943 I joined the guard team of the Neuengamme concentration camp. Some time later, I was assigned to the prisoner camp as kitchen chief, where I remained until the end. My last rank was SS-Oberscharführer.

Two former prisoners named Michael Müller and Jakob Beisiegel testified against me as witnesses for the prosecution. Müller had previously worked for some time in the prisoners‘ kitchen and then joined an external camp detachment. When he came back and wanted to work in the kitchen again, I refused. He was given a job at the delousing station. Out of resentment at being turned down, he testified in court that he had seen me slapping prisoners in the kitchen, even though he couldn’t possibly see what was going on in the kitchen from his place of work. –

Prisoner Beisiegel testified that, as a commandant’s office cleaner, he often had work to do in the SS kitchen. On such occasions, he had often listened in on telephone conversations between the SS kitchen chief Wendefeuer and me. Wendefeuer is said to have said (to me): „Can you leave me a carton of margarine? I’ll send a runner to pick it up right away.“ – This was followed by the allegation that food for prisoners had been illegally used to cater for the troops. –

In reality, however, the situation was different. The provisions room for all food was located in the prisoners‘ camp. The quantities needed for the troops were collected from there at certain times. If there was an unforeseen need (e.g. for major transfers etc.), Wendefeuer borrowed margarine from me, which was stored in large quantities in the cold store in the kitchen. However, these withdrawals were immediately charged back the next day. There was therefore no question of unlawful withdrawals. –

In an extensive speech, the prosecutor tried to charge me and my co-defendants with responsibility for alleged abuses from the period beginning in 1939, although I had only arrived in the camp at the beginning of 1943.

The British assigned me an official defence counsel at the trial. However, I refused this defence counsel because I had seen as a witness in the 1st Neuengamme Trial that the public defenders there only played the role of yes-men and did not help their clients in any way. After a short consultation, the court allowed me to defend myself.

The following incident is indicative of the „objectivity“ with which the court proceeded against us:

I had called the former Dutch prisoner Dr Albert Van de Poel, resident of Breda, Baronielaan 154, as a witness for the defence. Dr v.d. Poel stated on the witness stand: „Before I am asked any questions, I would like to formally thank the accused Oberscharführer Bladowski on behalf of all living and deceased prisoners of Neuengamme for the care he has shown us!“ –

This was probably the last thing the prosecutor and the court had expected. The consternation of the gentlemen was unmistakable. To get out of the affair, the presiding judge announced: „Five minutes break!“

At the resumption of the trial, when I wanted Mr v.d. Poel back on the witness stand, I was told that Dr P. was no longer there! In reality – as Dr v.d. Poel later informed me in writing – he had waited in vain all day in the witness room for his further questioning; he had only come to Hamburg by plane for this purpose! It is clear to me that Dr v.d. Poel’s further statement to me is completely true, that the British later caused him many difficulties, and all this only because of his courageous defence of me.(18)

On 10 July 1952, Bladowski’s lawyer wrote to the Office of the Legal Adviser, Wahnerheide, B. A. O. R. 19. I’ll provide the rather clumsy translation contained in the file and correct or add according to the original German text, also contained in the file.

In my capacity of defence counsil for Longin Bladowski who is at present at the Allied Prison at Werl I take the liberty of submitting you the following with the request that same be taken into consideration when instant case is reviewed.

On 13 July 1946, Longin Bladowski was condemned to death by the high British military court. The sentence was modified to imprisonment for 12 years on 26 October 1946.

Longin Bladowski is now 47 years old. He was born in the district of Danzig and, being a German national, he was called up for front service when the world war broke out. In 1943 he became unfit for front service and was transferred to the camp at Neuengamme. There, he was employed as chief of the kitchen and he continued to carry out that function until the end of the war.

The Dutch citizen Dr. Albert van de Poel has repeatedly intervened on behalf of Bladowski. Unfortunately, however, the witness Dr. van de Poel was not heard in an exhaustive way during the main trial. When this witness testified against Jakob Beisiegel, a witness for the prosecution, the examination of the witness van de Poel was suspended. But then he was never heard again.

I cannot do without giving a short characterization of the witness for the prosecution, Beisiegel. This witness was employed as „calefactor“ [„trusty“, in prison slang] in the camp commandant’s office. From an occasionally overheard telephone conversation, according to which margarine was to be left to the kitchen chief of the administration, called Wendefeuer, he meant to conclude that the prisoners were to be deprived of the margarine in question. A telephone conversation to that effect was possible since there was only one big cold-store in the camp which contained victuals both for the members of the administration and for the prisoners.

Above all the witness Dr. van de Poel, who had always peeled the potatoes during his stay at Neuengamme, is in a position to state that Bladowski has done everything possible for the prisoners and that he took care at any rate of their rations being supplied to them. In this connection I would refer to the statement of the witness Dr. van de Poel presented to the chief of the Legal Division at Herford in date of 1 August 1950. The statement reveals in detail what Bladowski did for the prisoners.

The statement of the witness Müller who, by the way, besides being a communist, appears to have been a professional witness for the prosecution, as he was to be seen in several trials, seems to be inspired by a certain amount of animosity. Before the year 1943, Müller had once been occupied in the kitchen of the camp. He was then removed but under the new chief of the kitchen, Bladowski, he wished to get his old job in the kitchen back. Bladowski had then been warned by other prisoners against Müller and he therefore refused to re-employ him in the kitchen.

It is a regrettable fact that similar trivial differences could lead to very severe sentences if the witnesses did not make their statements in an objective way but were inspired by feelings of hatred and revenge. In the past years it has been proven in a number of cases that the trials could not withstand a lawful and objective review if built up on the basis of witness statements which are objectively incorrect as the facts are therein distorted in a subjective way.

Inasmuch as mischiefs referring to the period from 1939 until 1943 should have come up in the trial, Bladowski is not responsible for them as he arrived at the Neuengamme camp only in 1943.

In relation to his personal affairs I would point out that also in consideration of Bladowski’s family a mitigation of his punishment appears to be justified. Bladowski is the father of three children at the age of 7, 11 and 14 years. His wife living at Gudendorf near Cuxhaven is facing extremely difficult economic problems. One of the children is still in Poland and the mother is lacking the necessary energy in making every possible attempt to get her child back. Bladowski’s release from imprisonment would greatly attribute to giving his family new hope for the future and help to develop his children into worthy human beings.

[Actually, the last sentence reads in the original: „If the family, especially the children, are to become people who do not despair of the future, only the release of Bladowski from prison can contribute to this.“](19)

The news about Bladowski’s son Jürgen, aged 7 (or 9, if his birth date is correct), still living in Poland in 1952 without his parents and siblings – that really hit me. Those kind of stories are well known, of course, and they weren’t rare. But how horrible is that? I do hope he was with family members, at least, or people who cared about him.

Bladowski’s lawyer also contacted Albert van de Poel again, and he wrote back to her on 2 August 1952 in his good but not perfect German (I love the Dutch!):

In response to your letter of 2 July, I would like to inform you that I would be happy to take up the case for Bladowski again.

The matter seems rather hopeless to me. Three times I have sent an application to the English authorities at Bladowski’s request. The reply came months later and was dismissive.

I have already said what I can say in favour of Bladowski. Moreover, I repeat that from personal experience during my imprisonment in Neuengamme (1941/1944), I can testify that Bladowski was good for Allied prisoners and that he was in good standing with these prisoners. I was so convinced of this that I recently approached the Belgian Minister for Public Works, Mr Bohogne [sic], who was also a prisoner in Neuengamme, to ask him for confirmation in favour of Bladowski; but as he was working in a detachment in Fusum and was housed there, he heard nothing about Bladowski in Neuengamme.

What else can I do? Of the Allied prisoners who knew Bladowski, as far as I know only the Polish Prince Jedzy [sic] Swiatopelk Czetwertynski is still alive, which I wrote about in my book about Neuengamme („Ich sah hinter den Vorhang“(20), which was published with the help of the English authorities) (in the last chapter), but I don’t know where he is living at the moment.

I see no reason why I should not have told the truth about Bladowski – whereas there are so many reasons to remain suspicious of the testimony of German prisoners against Bladowski. A simple proof of this – apart from the knowledge that often hatred and revenge animated the victims of the Nazi concentration camps after the war – is probably that one of the most distinguished witnesses in the English trials against the Nazi personnel of Neuengamme, called Schimmel [sic], whom I knew continuously during my two-year stay at Neuengamme as secretary to the camp elder, and who as a prominent person always enjoyed advantages denied to Allied prisoners, accused me to the prosecutor at the trial that I was in the service of the Gestapo. This only to cast suspicion on my testimony in the Bladowski trial.

A ridiculous, malicious suspicion plucked out of the air, which would of course be passed on to the Dutch authorities, but which has been set aside here without further ado as nonsense.

I do not know Bladowski’s dossier and I have never been given the opportunity by the English authorities to prove that the slander of Schimmel is nothing but blasphemy [Lästerung; van de Poel obviously meant lies or defamation – although he was a practising Catholic and had notions of becoming a priest in his youth!].

It is clear to me that a tragic error occurred in the Bladowski trial, but the response of the English authorities to my petition for clemency is, without more, that there is no reason to change the sentence after it was reduced from the death penalty to 12 years imprisonment.(21)

In her book, Geertrui van den Brink takes a closer look at the Schemmel affair (my translation):

„I testified under oath in favour of Bladowski because he has been good to allied prisoners. He was denounced by German prisoners because he (Bladowski, a Pole) did not help German prominent people in the camp.“ [states van de Poel]

But how does this positive testimony pan out? Former prisoner Herbert Schemmel, also a witness, is extremely surprised to see Albert in the uniform of a Civil Officer in the room. He is also going to give a statement under oath:

„When he had to register Albert in the administration system, it turned out that there was a vague and unclear ground for detention. He looks into the arrest warrant. Van de Poel is editor of a Dutch newspaper and has protested in this newspaper against the occupation of a place that belonged to the RC Church. None of the Dutch wants to associate with him. Immediately after entering, he tries to endear himself to the SS leadership and a few prisoners.“

Schemmel further states that he saw Albert handing out cigars and cigarettes, especially to Bladowski, a Kapo and to Dreiman [sic], the Rapportführer. Van de Poel received many parcels. In return, Bladowski let him work in the potato peeling kitchen for ten months, and this way Albert did not have to go to the external camp detachments. At the end of ’43, Van de Poel was released, a very rare and unusual measure.

In all, nine Dutchmen were released that year. A few months after his release, Dreimann entered the administration office with a letter from Van de Poel, addressed to him. The envelope and address mention the SD office in The Hague. Schemmel is allowed to see the letter, which states that Dreimann is thanked for the good treatment and his help in distributing parcels. And it even includes a parcel for Totzauer, Max Pauly’s Adjutant, with stamps because Totzauer collects them. It is abundantly clear that Van de Poel is either employed by the SD again or is very friendly with the SS. Dreimann says to Schemmel:

„Now you can see how far he has come! It is indicative of his attitude that he is not ashamed to portray Bladowski as an innocent lamb under oath. Although it has been proven by numerous witnesses that Bladowski is responsible for the deaths of many Dutch people and others. And even during this trial he gives Bladowski a package with food, tobacco, cigars and chocolate.“

Schemmel is well aware of this serious accusation against a Civil Officer and certainly wants to repeat it if necessary. Willie Dreimann is interrogated about this accusation (23 July 1946):

„I was in Wittenberge from 28 August 1942 to 4 December 1944 and I knew Van de Poel there. He got pneumonia and was then sent back to Neuengamme. He could no longer handle the heavy work. He received a package every two weeks. I have been offered many cigars, but only accepted one. I can no longer remember exactly whether Van de Poel’s letter was addressed to me.“

But Dreimann is very certain that Van de Poel was employed by the SD after his release. He does not doubt Schemmel’s testimony, he always worked correctly and accurately. Albert writes a response with comments and explanations about the claims. He refutes this course of events.

What could have happened?

As you read, questions arise. Did Schemmel know enough about the case and what did he see? He could view arrest warrants at the office, which was not possible for everyone. Everyone’s memory is selective, certainly not complete and Schemmel could not have known all the ins and outs of Albert’s case. He reconstructs based on his observations. Was Schemmel jealous? He had been imprisoned since 1939 and then he experienced someone else being released. He may even have had to type Albert’s notice of discharge! And he worked correctly and accurately. Yes, of course. To keep his office job. Also a form of survival. Dreimann downplays his own behaviour, he doesn’t exactly remember and has to make sure his punishment is light(er). The release, the collection service for H.J.Nelis, the sending of letters and parcels via the SD office in The Hague create a cloud of suspicion around Albert.(22)

Michael Müller, whom Longin Bladowski mentions in his letter, also appears in Geertrui van den Brink’s sources (my translation):

Wilhelm Dreimann, born in Hamburg in 1904, has worked in KZ Neuengamme since 1940. He became Rapportführer there (at the latest in 1944). A testimony about Willie Dreimann by Michael Muller [sic], ex-prisoner in Neuengamme from 1941 until the end of the war:

„In the Neuengamme camp he (Dreimann) was the terror of the prisoners. He took particular pleasure in cycling through the roll-call yard after work or on Sundays and, armed with a whip, randomly beat the prisoners standing there. He was one of the most hated SS men in the camp.“(23)

Let’s try to unpack some of the goings-on. I agree with Geertrui van den Brink’s conclusions about Schemmel, but then we have the strange chummy interaction between Dreimann and Schemmel at the trial. Schemmel, who

appeared as a witness in the Neuengamme main trial and other subsequent trials of the British military government. He also testified in almost all West German investigations and court proceedings in connection with the Neuengamme concentration camp. For decades, he gave talks as a contemporary witness for school classes and other events and led guided tours of the former concentration camp site(24)

is only too eager in 1946 to side with Dreimann, „one of the most hated SS men in the camp“, against Bladowski and van de Poel? While Müller, who has his own bone to pick with Bladowski, gladly gets Dreimann sentenced to death? What is going on here?

Also, let’s not forget that Albert van de Poel was released from Neuengamme in November 1943 while Leo Bladowski only started work at Neuengamme sometime in 1943. They didn’t know each other that long; so perhaps that also plays a role in the different perceptions of the prisoners.

If we put all those pieces of information together, we might actually get to the reason of why Longin Bladowski’s death sentence was not only not carried out for three months but then commuted to twelve years in prison. The British military court possibly refused Albert van de Poel as a witness for the defense after the accusations against him by Schemmel and Dreimann (although that does not excuse the lie they told Bladowski nor the fact that they did not inform van de Poel of their decision). The British then informed the Dutch authorities who started their own investigation into van de Poel and came up with nothing. The British, after learning that van de Poel was a credible witness after all, decided to take his testimony on behalf of Bladowski into account. That is my educated guess. It is sort of backed up by a letter:

To the secretary of the Appeals Council Mr J.B.W.P. Kickert, he writes:

The indictment dates from July ’46 at the Hamburg Tribunal and was issued by Schemmel, who resented the fact that, following a request from the British, he acted as a witness in favour of Bladowsky [sic], the former kitchen help at Neuengamme. I then immediately protested to the English court and requested an investigation from the Dutch consul-general A.J. Schrikker, and on my return informed Mr Woltjer, head of the Department of Justice. He prepared a report dated 22 July ’46. Statements were then received from four former prisoners. On 11 and 14 November ’46, Schrikker informed the Department of Foreign Affairs from Hamburg that Mr Van de Poel was completely exonerated and not at all to blame.(25)

At any rate, it seems that, this time around, van de Poel’s effort on behalf of Longin Bladowski was successful. As we have already seen, Bladowski was released from Werl on 7 May 1953. Before that, there was a bit of a bureaucratic hurdle to take: Apparently, there was some uncertainty about Bladowski’s citizenship. The Ministry of Justice in Bonn (capital of West Germany) had registered him as Polish, probably because the British prison authorities had registered him as such. Werl prison, however, informed them that he was, in fact, German.

He was born on 20 March 1905 in Rahmeln[sic]/West Prussia and did not opt for Poland during the period when West Prussia was under Polish administration.(26)

Following his release, Longin Bladowski was sent to the Fischerhof in Uelzen and, while there, not only got to know Savitri Devi but also came face to face with the realities of being an ex-convict, an ex-SS man and an ex-concentration camp employee in post-war Germany. He needed official approval in order to work – to even find work, for that matter. He had a son (who probably didn’t even remember him) in Poland. His wife obviously wasn’t well. So underneath his cheerful façade there must have been a lot going on.

Hans F. did not come to the Heimkehrerverband’s dancing party. Nor did Hans-Georg P. But Leo came. […]

Up till then, seeing how earnestly engaged in conversation I was, nobody had asked me to dance. Now a cavalier was standing before me: a tall, handsome man with steel-blue eyes that smiled to me: – Leo.

„But I don’t know how to dance!“ said I, hesitatingly. And it was true: I had never learnt to dance – save Greek folkdances. The only ballroom dance I somewhat knew was the waltz. And I had not danced even that for the last thirty years or so. But Leo did not believe me.

„Not even with me, – a comrade?“ asked he.

„Yes, I shall dance with you; I shall try…“ said I, getting up and smiling. And when I was standing close enough to him to be able to speak without anyone else hearing, I added „… with you, an S.S. man, who suffered for the sake of all I love.“

He gazed at me with an emotion that had nothing, absolutely nothing of the nature of desire, but that could be described as respect mingled with pride.

„I have done all I could,“ answered he. „And I have known what is man-made hell. And I am ready to fight again, not in order to regain what I have lost (there are things one cannot regain), but so that I might avenge our comrades who died in torture, with the Führer’s name upon their lips; avenge our now dismembered Reich, and build it up once more, stronger than ever, upon the ashes of those who destroyed it.“

I looked up to him, happy. „I like to hear you speak thus,“ said I. „I then feel that I am not alone in this land that I have called ‚my spiritual home.'“

„You are not alone; that I can tell you! In whose hearts can your words – your burning words ‚Never forget! Never forgive!‘ – find a better echo than in ours?“ And he pressed me to his breast as we whizzed around to the waltz music. (Fortunately for me, it was a waltz.)

[…] Then, I remembered that Leo B. had spent over seven months in the ‚death cell,‘(27) waiting to be hanged, before the British had commuted his sentence to one of life-long imprisonment. Like the others, he had been condemned to death for having obeyed orders, – for being a soldier. But he was alive – nay, very much, and in various ways alive, if I were to believe the stories that other comrades had told me about him. Alive, and faithful. And his vitality and his unflinching faithfulness defied the forces of ‚de-Nazification‘; were one of the numberless post-war individual victories of our Weltanschauung and of the tremendous unseen Powers of Light that stand behind it.

I could not help telling him so. „I am glad to feel you so strong and so alive in spite of all you went through,“ said I. „Every breath, every step, every movement of yours is a cry of triumph – a laughter of defiance – in the faces of those who wanted to kill you for having served the Third Reich with all your heart.“ […]

There was hope in Hans F.’s striving towards the perfection of the integral Nazi way of life; in his ideal of life without a weakness – hope, nay, even in the austere intolerance in the name of which he tried to impose his moral restraint on poor Leo. There was hope in the vitality of the men of iron; in their unbending will; and, among the best of them, in that clear consciousness of what National Socialism really means, and in the certitude of its eternity as an outlook on the world and as a scale of values.

(Savitri Devi: Pilgrimage)

I haven’t been able to find out what happened to Bladowski’s wife Viktoria. Did she die? Did they divorce? Be that as it may, sometime before 1966 Longin Bladowski married again, either Ursula Lemke or another Ursula. She is listed in the Hamburg telephone books as late as 1980. In 2001 and 2003, there is a U. Bladowski listed in the Oberursel telephone books – but I’m not sure it’s the same person.

(1) 1,78 m, according to his file BArch R 9361-III/252982

(2) BArch ALLPROZ 8/47

(3) https://media.offenes-archiv.de/ha1_3_3_thm_2335.pdf

(4) http://www.neuengamme-ausstellungen.info/content/documents/thm/ss5_1_1_thm_2144.pdf

(5) https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albin_L%C3%BCdke

(6) Carol Bowman: Children’s Past Lives, 1997. Kindle version, position 1704

(7) However, translated from Albert van de Poel, Ich sah hinter den Vorhang, p. 32-33: „Many a captured Pole or Russian was caught rummaging through the rubbish heaps, perhaps to find the stinking remains of spoilt kitchen waste. That was forbidden, of course. It was also against the rules. But on the emaciated body, or whatever skin, bones and intestines were left of it, it had a worse effect than opium, because it meant all kinds of diseases. And the pustules and ulcers soon shot up like poisonous mushrooms on the limbs of the „waste eaters“, who soon emitted an odour like a cesspit. They were mercilessly taken by the collar, beaten to a pulp and thrown, clothes and all, into a water container, a few buckets of water poured over their heads and finally chased off to work or to a remote corner of the camp with sticks and whips […].“

(8) https://media.offenes-archiv.de/ss4_1_2_bio_1789.pdf

(9) The information is drawn from Bundesarchiv file BArch R 9361-III/252982

(10) http://www.neuengamme-ausstellungen.info/content/documents/thm/ss4_2_3_thm_1806.pdf

(11) BArch B 305/6935.

(12) https://media.offenes-archiv.de/ss4_4_thm_1813.pdf

(13) BArch R 9361-III 252982

(14) https://www.google.de/books/edition/International_law_review/IbIvAAAAIAAJ?hl=de&gbpv=1&bsq=longin+bladowski&dq=longin+bladowski&printsec=frontcover

(15) Geoffrey P. Megargee: The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. Volume I: Early Camps, Youth Camps, and Concentration Camps and Subcamps under the SS-Business Administration Main Office (WVHA) (https://books.google.de/books?id=ndUAAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA1169&lpg=PA1169&dq=ursula+bladowski&source=bl&ots=iBx8qdptpQ&sig=ACfU3U0467MZoKkkjzDovGt7aDcRo3TY8Q&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiByKaplo-EAxVX8wIHHTcNBU04FBDoAXoECAMQAw#v=onepage&q=ursula%20bladowski&f=false)

(16) translated from Wolfgang Benz, Barbara Distel: Der Ort des Terrors Vol. 5: Hinzert, Auschwitz, Neuengamme (https://books.google.de/books?id=E0mG9tQy864C&pg=PA504&lpg=PA504&dq=ursula+bladowski&source=bl&ots=LRxik6_r9p&sig=ACfU3U2eMCWfRL99FYfEbQevbWiNQFvhBw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiByKaplo-EAxVX8wIHHTcNBU04FBDoAXoECAIQAw#v=onepage&q=ursula%20bladowski&f=false)

(17) I have the sinking feeling that this might have been the Marianne Kreuzer who was later involved with the Dominas gang in the 1960s…

(18) BArch B 305/6935

(19) ibd.

(20) „I looked behind the curtain“, the German translation of Neuengamme which was probably done from an English translation that was never published; at least I have been unable to find any evidence of it. But the English text is mentioned in the German edition. Geertrui van den Brink reports (my translation): „Another pressing question is whether work has already been done on the book in which their experiences will be told. Count George [Swiatopolk-Czetwertynski] brings Albert into contact with the British and two Intelligence Service officers come to question him at home about his past. Apparently everything is fine. In January ’45 Albert leaves for Heerlen to work for the Dutch Military Authority as a Press Officer.“ According to van den Brink, the Dutch edition was first published in Heerlen, so the English text was likely produced for the British authorities. The book had, of course, propaganda value.

(21) BArch B 305/6935

(22) BHIC 327 J.E.A. van de Poel, quoted in Geertrui van den Brink, Dr. Albert van de Poel, p. 204-205

(23) ibd., p. 206

(24) https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herbert_Schemmel

(25) BHIC 327, quoted in Geertrui van den Brink, Dr. Albert van de Poel, p. 248. It is strange that van den Brink keeps referring to Bladowski as a „Kapo“, a „kitcher helper“, etc. I don’t know if those expressions are actually used in her source material, or if she interprets the events in this light.

(26) BArch B 305/6935

(27) A curious piece of information. Savitri Devi can usually be trusted with details like that; however, we know from the files that Bladowski was sentenced on 13 July 1946 and had his sentence commuted on 26 October 1946. So what do the „over seven months“ refer to? Bladowski’s imprisonment before the trial and up to the reprieve in October?